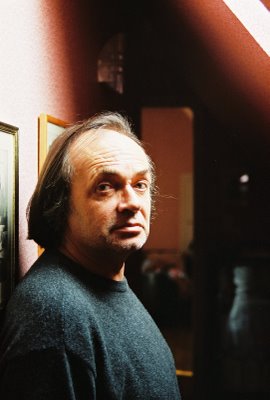

Editor Elizabeth Clark Wessel talks with emerging translator E.C. Belli.

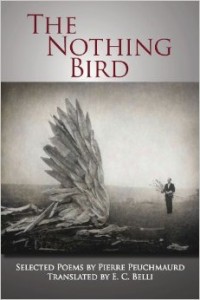

I was lucky enough to study translation with E.C. Belli at Columbia University, and I’ve been fascinated since then by her translation process, her fierce advocacy for the little known (in the U.S) French poet Pierre Peuchmaurd, and the work that has resulted from it. She has rendered the elemental, late surrealistic poetry of Peuchmaurd in an evocative, emotional English, and the collection she translated and edited is now available from Oberlin College Press. You can read more of Belli’s translations here.

How did you first become interested in translation and in the translation of poetry? And can you describe some of your first experiences with translation?

I suppose I’ve never experienced life without translation. I grew up speaking French with my Swiss father and my sister (in school as well) and English with my British mother. My mother was very firm about not letting us speak anything else than English with her as she wanted us to be bilingual. After living a day in French, I’d come home and attempt to recapitulate it all in English. It was constant and exhausting.

As for the translation of poetry and literature, I first became interested in it when I started reading poetry as a preteen. Three authors in particular: Edmond Rostand, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Victor Hugo. But really I think it began with Edmond Rostand (best known for Cyrano de Bergerac): a teacher in junior high school, Madame Vera, gave me his out-of-print book Les Musardises. His poem “Le Petit Chat” had charmed me and I kept going on about it in class. She just pulled out this old book for me one day and sent me home with it. It was my first treasure.

I then discovered Rostand’s play, L’Aiglon, based on the life of Napoleon II (later called the Duke of Reichstadt). Specifically, an unfinished poem from 1894 that was featured in the supplementary materials. It’s called “Un Rêve” (a few lines actually made it into the fifth act of the play): the Duke and Seraphin Flambeau, an old soldier from Napoleon 1st’s Army, stand in a field after Flambeau has struck himself with a sword to avoid being taken alive by the police. In his dying haze, Flambeau imagines he is back at the Battle of Wagram and is dying an honorable death from battle-related wounds. The Duke joins him in his reverie and sees the field fill with dead and dying men, and finds himself helpless amid this widespread suffering. It’s so beautiful and dark and tragic.

I remember wanting, very badly, to translate “Un Rêve” for my British relatives, in particular my grandmother, who is a poet. I’d go at it line by line, on the fly, doing the best I could. Sometimes something magic happened and a line came to life, but more often than not it fell completely flat. It was very frustrating. Two years ago, I wrote an “adult” translation of the poem during a class. It has a lot of problems, but I love it and keep going back to it to make changes. It’s my secret project. I suppose that was my first experience with ‘real’ translation.

What attracts you to a certain project? And specifically, how did you come across the work of Pierre Peuchmaurd?

Oh, I’m hopeless. Love, death, and the carnal! I end up with terrible crushes on projects. And writers. They are often formally innovative and always very charming. I think I literally fell in love with Peuchmaurd when I first read him. I discovered his poem “It Will Come in My Left Lung,” shortly after his death, on the French poetry blog Poezibao. I just wept and wept, even though I didn’t know him. I then went on a rampage and devoured “A Treatise on Wolves” after which I bought all of his books. They were very hard to find. A lot are out of print. But his son, Antoine, has a bookstore in Montréal, Librairie Le port de tête, where he keeps a lot of his father’s works. Check them out on Facebook.

Oh, I’m hopeless. Love, death, and the carnal! I end up with terrible crushes on projects. And writers. They are often formally innovative and always very charming. I think I literally fell in love with Peuchmaurd when I first read him. I discovered his poem “It Will Come in My Left Lung,” shortly after his death, on the French poetry blog Poezibao. I just wept and wept, even though I didn’t know him. I then went on a rampage and devoured “A Treatise on Wolves” after which I bought all of his books. They were very hard to find. A lot are out of print. But his son, Antoine, has a bookstore in Montréal, Librairie Le port de tête, where he keeps a lot of his father’s works. Check them out on Facebook.

After becoming so familiar with his work, how did you approach putting together a single collection to introduce him to American readers?

Well, I translated “It Will Come in My Left Lung” first. Then I translated “A Treatise on Wolves.” I continued to read Peuchmaurd and every time I found a new poem I fell in love with, over the course of three or four years, I’d translate it.

It was my way of engaging with it on the deepest possible level. To feel it in every fiber of my being. I needed a physical relationship with this writer, something I could only get by carrying his words around with me, by having them tumble around in my mind.

I ended up performing a mostly thematic progression through his poems. I’d find a whole bunch of poems he’d written on life in the countryside, stop there for a bit, translate my favorites, and then find some on death, and then stop there, and so on. And that’s what ties the book together, I think. It makes a lot of sense to me emotionally. I’m very attached to each poem, as though they were people. The book is like all my favorite people in a room.

Do you have any advice for young translators?

There are a few things that have become personal truths over the course of my projects, but I am weary of ‘great truths’ that should apply across the board. Everyone finds their own style. (By the way, I totally consider myself a “young” translator. Has 30 pushed me over the edge? Say it isn’t so!):

- For prose, mostly: The first few pages are hard. I sometimes dislike the book initially. I wonder if I can do it. Perhaps I am not smart enough. Perhaps my knowledge is too limited. I tear the book into smaller more manageable sections. I go at it like some ant, little by little, carrying the loads over. The process is laced with disappointment and very small victories at first. It takes a while to take off. It’s different of course if you’re putting together a collection and translating individual poems first.

- Don’t underestimate your power to affect the American literary landscape. You may find an extraordinary writer you fall in love with. You may translate her or him, for some years, without any of the work going anywhere. You may query a press you’ve long admired on the bookshelves. And you may be holding the book in your hands some months later wondering what act of providence made all of this possible. What greater prize is there than enriching the cultural landscape of the country you live in? Of bringing over a little piece of home and carving out a space for it?

- Fall in love with the writer, their poems, their prose. It’s a better translation if it’s a love affair.

- Review other translations. You’ll not only help bring awareness to translated books, but you’ll also learn tricks from other translators when you discover books that you might not have reached for yourself. I discovered so many gems that way.

- I like to translate by hand. (Is that what pushed me out of the “young” translator zone?)

- I like to read what I translate out loud.

- I like to type it up and then have it printed before making edits so that it looks like an actual book. Like something serious. It helps me envision it as a book in all of its physicality and then helps me nail down the tone. It really helps me make the transition from translation to editing if the work undergoes a substantial physical change.

- When I can, I try to translate every day. I’ve always felt it’s like a muscle, just like writing. It’s good to keep going once you’ve found your pace.