Three poems by Macario Matus translated from Zapotec into Spanish by the author, with English translations and an introduction by Wendy Call.

In Mexico’s southern state of Oaxaca, twenty miles north of the Pacific Ocean, the city of Juchitán has produced an enormous constellation of musicians, poets, storytellers, and painters. Juchitán’s traditional language, Isthmus Zapotec, was the first New World language to be written down, more than two thousand years ago. Over the last century, many bright lights of indigenous literature have come from Juchitán. Macario Matus was one of the most prominent; he influenced an entire generation of Zapotec storytellers and poets. One of those poets, Irma Pineda, said of Matus, one year before his death in 2009, “Macario Matus is in my life like water, like daylight. He exists, has always existed. I can’t pinpoint the date that we met; no one introduced us for the first time. And yet, every day I discover him, I recognize him, because every day he invents something new, something surges forth from that imagination—abundant, terrible, tireless, ferocious.”

In Mexico’s southern state of Oaxaca, twenty miles north of the Pacific Ocean, the city of Juchitán has produced an enormous constellation of musicians, poets, storytellers, and painters. Juchitán’s traditional language, Isthmus Zapotec, was the first New World language to be written down, more than two thousand years ago. Over the last century, many bright lights of indigenous literature have come from Juchitán. Macario Matus was one of the most prominent; he influenced an entire generation of Zapotec storytellers and poets. One of those poets, Irma Pineda, said of Matus, one year before his death in 2009, “Macario Matus is in my life like water, like daylight. He exists, has always existed. I can’t pinpoint the date that we met; no one introduced us for the first time. And yet, every day I discover him, I recognize him, because every day he invents something new, something surges forth from that imagination—abundant, terrible, tireless, ferocious.”

Born January 2, 1943 in Juchitán, Macario Matus moved to Mexico City as a young adult to study; he continued to migrate between the two cities throughout his life. Matus published his first book at age 26, eventually producing more than twenty volumes of poetry, short stories, journalism, criticism, history, and translations. He founded Juchitán’s Casa de la Cultura, the cultural center where multiple generations of juchiteco musicians, painters, and writers—like Irma Pineda—took their first art classes.

Matus passed away on August 6, 2009, at the age of 66. Three months after his death, a center for Isthmus Zapotec culture opened in Mexico City—a project of Matus’s for the last six years of his life. “Centro Cultural Yo’o Za’a Macario Matus” offers workshops taught by writers and artists who were students in Juchitán’s Casa de la Cultura under Matus’s leadership.

Unlike Irma Pineda, I never met Macario Matus in person. But like her, his work seems to have been around me, in the air and water, since my first visit to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in 1998. I discovered the bilingual poem “Bidóo Bacáanda / Dios del Sueño” (“God of Dreams”) in the Mexico City newspaper La Jornada, in June 2001. I don’t remember where I first encountered “Bidóo Gubéedxe / Dios de la Lujuria” (“God of Lust”) or “Cáa Bidóo Stíi Dúu / Dioses Nuestros” (“Our Gods”). All three poems appear in Matus’s 1998 collection Binni Záa (Los Zapotecas), but I’m sure that’s not the first place I read those poems. Books are still relatively rare and precious in Juchitán. By the time I borrowed a copy of Binni Záa, long since out of print, from Juchitán’s Casa de la Cultura, those poems were already familiar to me. In Juchitán, individual poems are passed around hand to hand, ear to ear. They flow through life like water, like daylight.

–Wendy Call

Bidóo Gubéedxe

by Macario MatusGuennda rigúu béedxe páa cáa guennda ranna xhíi

guláaqui cáa bée láa rigúu béedxe béedxe guíixhi.

Béedxe guíixhi, láani.

Guennda ráaca díiti máani stíi binni síica máni dúuxhu.

Xhiñée quíi gáaca núu síica béedxe guíixhi

páa láa núu gúule núu ndáani dúuxhu mée yáa.

Guennda ranna xhíi rudíi láa síica béedxe zée xpiáani.

Guennda ranna xhíi ngáa láaya béedxe náazi yanni.

Guennda béedxe ngáa ranna xhíi guiráa xhíixhe láaya binni,

guíidi láadi, bixhúuga náa máani, bixhúuga náa binni, guíicha

ruáa binni, guiée lúu béedxe ndáani yóo.

Guennda ranna xhíi née cúu béedxe ngáa ráaca binni máani née

binni guíidxi layúu.

¿Xhíi guiráa guíidxi layúu née cáa xpidóo lá?

guennda ranna xhíi née guennda rigúu béedxe zuzuhuáa cáa

huaxhíini, ridxíi.

God of Lust

by Macario MatusLove or lust

they called a wild tiger’s excesses.

Or an ocelot.

Men shiver instinctively,

like ferocious animals.

How could we not be like ocelots

if born of their spirited viscera.

Love is mad cats in heat.

Love is eyeteeth threaded into your neck

Lust is loving with all your teeth,

skin, claws, fingernails, whiskers, cat’s eyes.

To love and be lustful is to be animal, or man.

To lust and to kiss is to be woman with sugared bile.

When the earth and its gods meet their end,

love and lust will preside over night, over day.

translated from Zapotec by Wendy CallDios de la Lujuria

by Macario MatusLa lujuria o el amor

lo llamaron excesos del tigre silvestre.

Ocelote, pues.

Estremecimientos instintivos

de los hombres como animales fieros.

Cómo no íbamos a ser como ocelotes

si nacimos de sus entrañas briosas.

El amor es entrega de felinos a lo loco.

El amor es colmillos ensartados al cuello.

Lujuria es amar con todos los dientes,

pieles, garras, uñas, bigotes, ojos de gato.

Amar y ser lujurioso es ser animal u hombre.

Lujuriar y besar es ser mujer con hiel azucarada.

Cuando se acabe la tierra y sus dioses,

el amor y la lujuria presidirán la noche, el día.

translated from Zapotec by Macario Matus into SpanishCáa Bidóo Stíi Dúu

by Macario MatusNdáani cáa guiée nabáani tíi bidóo stíi dúu,

ndáani tíi yáaga nabáani tíi bidóo stíi dúu,

xháa xcúu nabáani xpidóo dúu,

ndáani níisa dóo née níisa guíigu

nabáani cáa bidóo bizibáani láa dúu.

Níiza guiée xhúuba, béedxe, béeñe

náaca cáa xpidóo dúu, bixhóoze née bíichi cáa dúu.

Guidúubi guíidxi layúu ngáa jñáa dúu.

Our Gods

by Macario MatusIn every stone lives one of our gods,

in every tree dwells one of our gods,

our god lives under the roots,

within the water of river and sea,

dwell the gods who gave us life.

Rain, corn, jaguar, and lizard

are gods, fathers, brothers and sisters.

All of nature is our mother.

translated from Zapotec by Wendy CallDioses Nuestros

by Macario MatusEn cada piedra vive un dios nuestro,

en cada árbol mora un dios nuestro,

bajo las raíces vive nuestro dios,

entre las aguas del mar y del río,

moran los dioses que nos dieron vida.

La lluvia, el maíz, el tigre, el lagarto

son dioses, padres y hermanos.

La naturaleza toda es nuestra madre.

translated from Zapotec by Macario Matus into Spanish

Bidóo Bacáanda

by Macario MatusGuúzi Góope síica Moctezuma guníi xcáanda

cáadxi binni quíichi née ruáa ráaxhi

zéeda yéete cáa lúu níisa dóo tíi quíiñe ntáa láa.

Née huandi, lúu cáa baláaga quée, déeche cáa máani quée veda

ndáa cáa binni guníi xcáanda xaíique quée.

Núu ndáani layúu stíi xaíique quée záa quée bíini núu xipiáani

riníi xcáanda cáa.

Rúuya cáa síica ráaca ridxíi níi chíi guizáaca lúu.

Cáa bacáanda quée, guníi zéeda quée, náaca cáa níi huandíi

néexhe náa.

Nguée rúuni quíi nucáa lúu cáa bée, bidíi cáa bée guíiba gúuchi,

layúu, née lúuna rizáaca.

Cáa bacáanda ngáa díidxa huandíi. Tíi gúuca huandíi guennda

ruziguíi stíi cáa binni quíichi.

Yanna láaga xhuxháale lúu núu riníi xcáanda núu huandíi ngáa

huandíi.

God of Dreams

by Macario MatusGúuzi Góope, like Moctezuma, dreamed

that some bearded white men

would come from the sea to dethrone him.

And yes, they arrived on huge ships, riding horses,

those men who the king had dreamed.

In the Zapotec kingdom there were wise men who dreamed.

They saw, clear as day, what soon would happen.

The dreams, they foretold, are waking realities.

And so they surrendered, handing over gold, land, and kingdom.

Dreams are real. The white men’s lie was real.

Now that we have awakened, we dream that truth is real.

translated from Zapotec by Wendy CallDios del Sueño

by Macario MatusGúuzi Góope, como Moctezuma, soñó

que unos hombres blancos y barbados

bajarían de los mares para destronarlo.

Y sí, sobre unas barcazas, sobre unos caballos,

llegaron aquellos hombres que había soñado el rey.

Había en el reino zapoteca los sabios que soñaban.

Veían como si fuera de día lo que pronto sucedería.

Los sueños, predijeron, son realidades despiertas.

Por eso se entregaron, dieron el oro, su tierra, reino.

Los sueños son verdad. Fue verdad la mentira de los blancos.

Ahora que estamos despiertos, soñamos que la verdad es verdad.

translated from Zapotec by Macario Matus into Spanish

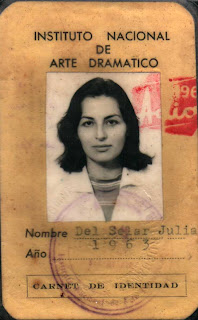

Photo of the author courtesy of Irma Pineda.