Three poems by Abraham Sutzkever translated by Maia Evrona

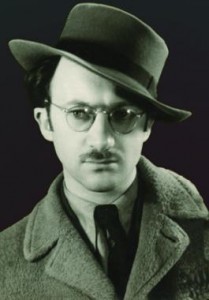

I’m grateful for the opportunity to publish my translations of Abraham Sutzkever, now, at this fraught moment for the treatment of refugees in the United States and larger world, as Abraham Sutzkever was something of a double, or even triple refugee. Born in what is now Belarus in 1913, he was forced to flee World War I with his family as a toddler, going, of all places, to Siberia. These days, we primarily associate Siberia with the Gulag, but for Sutzkever, it was a magical place, particularly when seen through the resilient eyes of a child, though his father passed away during the years his family sought refuge there.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to publish my translations of Abraham Sutzkever, now, at this fraught moment for the treatment of refugees in the United States and larger world, as Abraham Sutzkever was something of a double, or even triple refugee. Born in what is now Belarus in 1913, he was forced to flee World War I with his family as a toddler, going, of all places, to Siberia. These days, we primarily associate Siberia with the Gulag, but for Sutzkever, it was a magical place, particularly when seen through the resilient eyes of a child, though his father passed away during the years his family sought refuge there.

Later, Sutzkever survived the Holocaust in Vilna, first as a prisoner in the Vilna Ghetto, along with the rest of Vilna’s Jewish community, and then as a partisan in the forests, before he and his wife were finally rescued and brought to Moscow at the urging of the Russian poets Ilya Ehrenberg and Boris Pasternak. Following WWII, with violent anti-semitism still very much alive in Poland, and repression in the Soviet Union, Sutzkever understood that he could not remain in Eastern Europe and he and his wife immigrated, illegally, to Mandatory Palestine, just on the eve of the founding of the State of Israel and subsequent war. There, he had a brother (his only remaining immediate family, apart from his wife and newborn daughter). In Tel Aviv, Sutzkever continued to write in Yiddish, despite significant prejudice toward the language within Israel, and a worldwide Yiddish readership now drastically smaller due to the Holocaust. These three poems were published in the expand ed edition of his collection Poems from My Diary, published in 1985.

ed edition of his collection Poems from My Diary, published in 1985.

Today’s refugee crisis is certainly not identical to the experience of the Jewish people during WWII, but I hope that won’t stop readers from drawing on Sutzkever’s memories of being a child refugee, his experience as the survivor of a catastrophe in which most perished, and his reflections on what we lose when we close ourselves off to the travelers outside, when addressing the crises of our time.

— Maia Evrona

Two in One

by Abraham SutzkeverI am two in one. One lives a long life in honor

of another and counts the stars for him until dawn.

I am two in one. One forged to the other forever,

if forever will allow Russian cubits to be its measure.

An enemy and a friend in one. And sometimes two enemies

who challenge one another to old-fashioned duels. And it turns out

that both get away with wounds and are left on the ground

riddled with bullets, until they lick the blood from themselves with a song.

And again a black cat may spring up or a frog,

we’ll stay, unintentionally, two in one from now on.

We know the double-hatred will not divide us,

that two-as-one are beating on the gate to heaven.

I am two in one. One dreams for the other. Let us free

our two-ness peacefully from the bars. And drink up

the summer sun to its last drop, let’s do that, as Socrates

drank all the way to the bitter end his poisoned cup.

translated from Yiddish by Maia Evrona“Now, Why is it That You Never Mention Your Siberian Father in This Diary?”

by Abraham Sutzkever“Now, why is it that you never mention your Siberian father in this diary?”

A question came. And instead of an answer, just see:

Before my eyes his skin has grown over mine,

and his beard has ripened on me, before my eyes.

Now your son has wholly become that reclusive being—his father,

with his fingers I roll soft tobacco in cigarette paper,

the night sits on a sparkling polishing wheel, rose colored and pure.

Where did I learn page after page of Gemora by heart?

Where did I learn to play the violin? With his fingers, I play

on otherworldly strings with the memory of the Garden of Eden.

Filled with sparkling ice, whose is this shovel?

With his big-boned fingers I’m playing his fiddle.

We exist eternally in the same mass,

the old snow has young strength, both to be covered in snow,

no guns nor artillery can separate us now.

*

“Now, why is it that you never mention your Siberian father in the diary?”

translated from Yiddish by Maia EvronaGone the Window And Through it the Poor Sabbath Guest, the Cherry Tree

by Abraham SutzkeverGone the window and through it the poor Sabbath guest, the cherry tree,

who came to stay the night with me along its journey.

Gone the cherry tree made of stars, they have all been stolen

by cosmic thieves.

This drilled hole has only left me as a vestige

a token amount of heavenly air, which had come in through that window,

brilliant

and four-sided.

That token of heavenly air, which had drifted in through that window

has been stolen by no one, nor shot to pieces.

The vision of my life owns a spacious home

inside four slender, slender lines.

And the greatest wonder of all: the cherry tree drifts in

to spend the night with me as it did then, that guest,

and the cherry tree made of stars, too, finds its way inside

through those same sweet slender, slender lines.

translated from Yiddish by Maia Evrona

Though I disagree with you on your stance on the refugee crisis (I support strong borders and believe resettlement is a mistake with dire consequences), I am thankful for your translation of Sutzkever’s work. A Rege is gefalen wie a Stern…