Mary Jo Bang speaks with E.C. Belli about the process of carrying this epic journey over into our English.

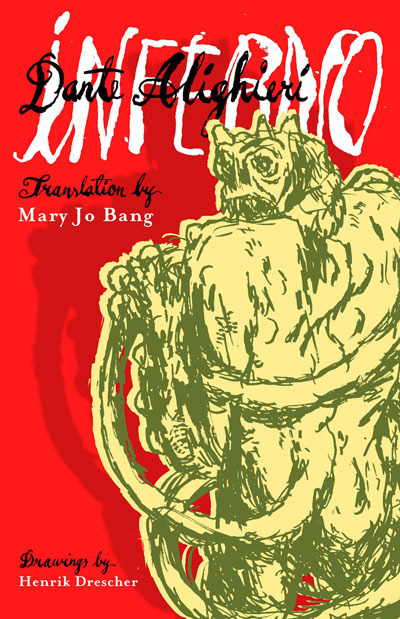

As if to leave a voice echoing in the hallway of years, as if to say This is now, This is us, Mary Jo Bang presents a volume of Dante’s Inferno that has gnawed at and digested the elements of our present. The filth, the grime, the greed is ours. We recognize it: it bears the marks of our today.

We know what purists will say—and yet Mary Jo Bang has done the most American thing you can possibly do: she has shown up to the fancy dress party in jeans and a white t-shirt screaming, We are allowed here too! This is our space to fill also.

What we have to thank Bang for above all is her willingness to break the sacrosanctity of an epic that has been held, for all these years, at arm’s distance, sheepishly, faithfully, terrorizing for its blue blood.

With an introduction that leads the reader, step by step, through the circles of hell before she experiences, as Bang puts it, her “Mind and body caught midmotion in the unfathomable,” and a translator’s note pearled with insights on Bang’s meticulous process, this Inferno calls to the reading public with generosity, telling to creep out, for a minute, of the large print sorcery, the emotional pornography, and the dystopias, and bask in a sublime classic.

E.C. Belli: Different translators have different methods. How did you approach this text? How did you start? Basically, what were your steps?

Mary Jo Bang: I would begin translating each canto by reading William Warren Vernon’s two-volume Readings on the Inferno of Dante: Based upon the Commentary of Benvenuto da Imola and Other Authorities. That 1906 literal prose translation traces the commentary on the poem, line-by-line, all the way back to Benvenuto, a lecturer at the University of Bologna who was born shortly after Dante died and whose commentary on the Divine Comedy was one of the earliest. I would then read Charles S. Singleton’s prose translation done in 1970, and then John D. Sinclair’s from 1954, examining the small differences between the two. Then I’d often go back to the Vernon to see what choice he’d made at the same moment, and I would re-read the surrounding commentary.

I think what is gained in this new translation is this sense of contemporaneity. The cost of achieving that was that I had to sacrifice, here and there, a strict allegiance to the original.

At some point in the process, I’d begin my own translation and then eventually stop to compare my attempt to other translations, primarily (but not limited to) those done by: Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, Mark Musa, Allen Mandelbaum, Michael Palma, and Ciaran Carson. If I still had any questions, I’d do a word-by-word dictionary translation for that tercet and the surrounding ones using the Sansoni Italian/English English/Italian dictionary. Sometimes I would do entire pages of word-by-word dictionary translation.