1. Mirror Trick

Of course I know her.

She is one and many,

A multitude flashing on, then

Blinking off—on, off—

Watching out from the tidy blank

of her face. She is silent, speaking

With just her mind. She is flesh, a form,

but also flat, a mute screen.

What she offers you, by no means

Should you accept. She belongs to no-one,

sitting like a ghost beyond her own reach.

And yet, she’s there—I mean me—

Behind glass, as if the world has been cleaved,

Though something whole remains,

Roving, free, a voice with poise and pitch.

She’s there—me—snug in the glass,

The little mirror on the bedside

Doing its one trick

A hundred times a day.

You didn’t come to live with me.

2. Turkish Bath

The room is choked with nudes.

Once, a man barged in by mistake

Crying, “Turkish bath!” He had no idea

My door is always locked in this heat,

No idea that I am the sole guest and client,

The chief consort, that I cast my gaze

Of pity and absolute pride across

The length of my limbs—lithe, pristine—

The bells of my breasts singing,

The high bright note of my ass,

My shoulders a warm chord

The chorus of muscle that rings

Ecstatic. I am my own model.

I create, am created, my bed

Is heaped with photo albums,

Socks and slips scatted on a table.

A spray of winter jasmine wilts

In its glass vase, dim yellow, like

Despondent gold. Blossoms carpet

The floor, which is a patchwork

Of pillows. Pick a corner sleep in peace.

You didn’t come to live with me.

3. Curtain Habit

The curtain seals out the day.

Better that way to let my mind

See what it sees (every evil under the sun),

Or to kneel before the heart, quiet king,

Feeling brave and consummately free.

Better that way to let all that I want

And all I believe swarm me like bees,

Or ghosts, or a cloud of smoke someone

Blows, beckoning. I come. I cry out

In release. I give birth

To a battery of clever babies—triplets,

Quintuplets, so many all at once.

The curtain seals in my joy.

The curtain holds the razor out of reach,

Puts the pills on a shelf out of sight.

The curtain snuffs shut and I bask in the bounty

Of being alive. The music begins.

Love pools in every corner.

You didn’t come to live with me.

4. Self-Portrait

The camera snaps. Spits me out starkly ugly.

So I set out to paint the self within myself.

It took twelve tubes, blended to a living tint,

Before I believed me. I named the mixture Color P.

The hair—curious, unlikely—is my favorite,

The same fluff of bangs tickling my niece’s face.

And my eyebrows are wide as hills. They swallow everything.

They were a feat. They do not impress me as likely to age.

They are brimming with wisdom. Neither slavish nor stern.

Not magnificent, but not the kind made to crumple in shame.

Not prudish. Unwilling to arch and beckon like a whore’s.

They skitter away from certainties like alive or dead.

My self-portrait hangs on the narrow wall,

And I kneel down to it every day.

You didn’t come to live with me.

5. Impromptu Party

The little table is draped with a festive cloth, and

Light blurs out from a single lamp, making us fuzzy.

A sip of red wine, and I rise to my feet. We are

Dancing, my guests and I, like kids in a ballroom.

We don’t smile or even speak. We’ve had a lot to drink.

To a single woman, time is like a scrap of meat:

Nothing you can afford to give away. I want

To hold it in my lap, Time, that sneak, that thief already

Scheming to break free. Please—I beg

Upon the magnificent extravagance of my beloved stilettos,

I want the world back. I’ve been alive—could it be?—

Near a century. My face has closed up shop.

My feet are a desolate country.

For a single woman, youth is a feast that lasts

Only until it is gone.

You didn’t come to live with me.

6. Invitation

When it arrived, I was interrupted by relief,

Sitting in my rattan chair, feeling the wind ease in

Through the hole in my life.

I only said yes because of his dissertation. Friends,

Nothing more. We talked—he talked—about modernism,

Black humor. But always at a distance from reality.

Why didn’t he ask anything of me?

Tender and petulant, he struck me as cute.

But at heart, only a very well-behaved boy.

He offers his arm. Elegant, decent, gallant.

But how can I prove myself a woman

If he is a child? What can come of that union?

Can any of us save ourselves? Save another?

You didn’t come to live with me.

7. Sunday Alone

I don’t picnic on Sundays.

Parks are a sad song; I steer clear.

But I dug out all my sheet music,

I lolled about in the Turkish Bath

Singing from breakfast to tea.

With my hair, I sang Do

And my eyes, Re

And my ear sounded Mi

And my nose went after Fa

My face tilted back and out rose Sol

My mouth breathed La

My whole body birthed Si

Like my cousin said, famously—

Music is the soul sighing.

Music pushes back against pain.

Solitude is great (but I don’t want

Greatness). My eyes slump

Against the walls. My hair

Hurls itself at the ceiling like a colony

Of bats.

You didn’t come to live with me.

8. Dialectic

I read materialist philosophy—

Material ispeerless.

But I’m creationless.

I don’t even procreate.

What use does the world have for me

Here beside my reams of cock-eyed drafts

That nick away at the mountain of

Art and philosophy?

Firstly, Existentialism.

Secondly, Dadaism.

Thirdly, Positivism.

Lastly, Surrealism.

Mostly, I think people live

For the sake of living.

Is living a feat?

What will last?

My chief function is obsolescence.

Still, I send out my stubborn breath

In every direction. I am determined

To commit myself to a marriage

Of connivance.

You didn’t come to live with me.

9. Downpour

Rain hacks at the earth like an insatiable man.

Disquiet, like passion, subsides instantly.

Six distinct desires mate, are later married.

At the moment, I want everything and nothing.

The rainstorm barricaded all the roads. Sandbags.

Isn’t there something gladdening about a dead-end?

I canceled my plans, my trysts, my escapes.

For a moment—I almost blinked and missed it—the storm

Stopped the clock that chases me. The clock of the heart, maybe.

It was an ecstasy so profound…

“Ah, linger on, thou art so fair!”

I’d rather admit despair. And die.

You didn’t come to live with me.

10. Dream of Symbolism

I occupy the walls that surround me.

When did I become so rectilinear?

I had a rectilinear dream:

The rectilinear sky in Leo:

The head, for a while, shone brightest.

Next the tail. After a while

It became a wild horse

Galloping into the distances of the universe,

Lasso dragging behind, tethered to nothing.

There are no roads in the black night that contains us.

Every step is a step into absence.

I don’t remember the last time I saw

A free soul. If she still exists, fire-eyed gypsy,

She’ll die young.

You didn’t come to live with me.

11. Birthday Candles

They are like heaps of stars.

My flat roof is like a private galaxy

That stretches on stubbornly forever.

The universe created us by chance,

Our birth a tidy accident.

Should life be cherished or lavished?

Showered with confetti or pelted with rocks?

God announces: Happy Birthday.

Everyone raises a glass and giggles audibly.

Death gets clearer in the distance. Closer by a year.

Because all are afraid, none is afraid.

It’s pity how fast youth sputters and burns,

Its flame like the season’s last peony.

A bright misery.

You didn’t come to live with me.

12. Cigarette

I lift it to my lips, supremely slim,

Igniting my desire to be a woman.

I appreciate the grace of the gesture,

Cosmopolitan, a shorthand for beauty,

The winding haze off the tip like the chaos of sex.

Loneliness can be sweet. I re-read the paper.

The ban on smoking underway

Has gotten a bonfire of support. A heated topic,

Though I find it inflammatory. A sputtering drag.

A contest between low-lives and sophisticates,

Though only time knows which is which.

Tonight I want to commit a victimless crime.

You didn’t come to live with me.

13. Thinking

I spend all my spare time doing it.

I give it a name: walking indoors.

I imagine my life is a melodrama

In which I possess all that I lack.

I flesh-out storylines. What never

Happens becomes a waking dream,

The kind that gets revealed at season’s end.

It’s impossible to think of everything.

Thinking of what I am afraid to say

Keeps my better judgment at bay.

I lose track. I look up, allowing thoughts

To collect. It is like having a garage

Full of props from a period movie.

It is like a republic with exacting rules

Regarding departure and re-entry. My visa’s

In-process. I want to settle, though like anyone,

I worry it’s overpopulated already.

You didn’t come to live with me.

14. Hope

This city of riches has fallen empty.

Small rooms like mine are easy to breech. People

Have taken to bodyguards, guardians. Still,

I come and go, always alone, fat with fear.

My flesh has forsaken itself.

Strangers’ eyes drill into me till I bleed.

I beg God: make me a ghost.

Something invisible blockades every road.

I wait for you night after night with a hope beyond hope.

If you come, will nation rise up against nation?

If you come, with the Yellow River drown its banks?

If you come, will the sky blacken and bleed?

Will your coming decimate the harvest?

There is nothing I can do in the face of all I hate.

What I hate most is the woman I’ve become.

You didn’t come to live with me.

translated from Chinese by Changtai Bi & Tracy K. Smith

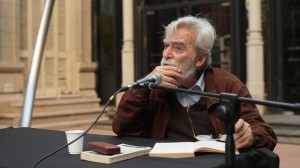

Two poems by Juan Carlos Mestre translated by Patrick Marion Bradley.

Two poems by Juan Carlos Mestre translated by Patrick Marion Bradley.