In this series Montana Ray talks with translators about their process and poetics. Ray will explore and challenge our understanding of the craft and its role in contemporary literature.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

In this episode celebrated translator and essayist Eliot Weinberger tells how he came to translate Octavio Paz and Bei Dao and talks about the process of translating their work. He discusses how waves of translation in the US have been spurred by changing political realities, and how those translations have impacted contemporary American poetry. The conversation also includes Weinberger’s thoughts on the deeper role of translation, both as a social function (bringing something new into your own language) and as an act (reaching for the inaccessible, unnamable).

In this episode celebrated translator and essayist Eliot Weinberger tells how he came to translate Octavio Paz and Bei Dao and talks about the process of translating their work. He discusses how waves of translation in the US have been spurred by changing political realities, and how those translations have impacted contemporary American poetry. The conversation also includes Weinberger’s thoughts on the deeper role of translation, both as a social function (bringing something new into your own language) and as an act (reaching for the inaccessible, unnamable).

With music by Cha cha, AM444, and 新裤子, plus an essay by Eliot Weinberger and poems and readings by Bei Dao and a poem by Octavio Paz with translations by Weinberger.

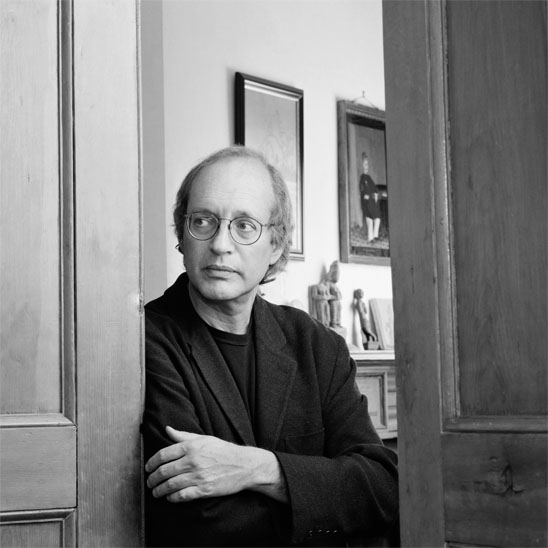

Eliot Weinberger’s books of literary essays include Karmic Traces, An Elemental Thing, and Oranges & Peanuts for Sale. His political articles are collected in What I Heard About Iraq– called by the Guardian the one antiwar “classic” of the Iraq war– and What Happened Here: Bush Chronicles. The author of a study of Chinese poetry translation,19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, he is the current translator of the poetry of Bei Dao, and the editor of The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry and a forthcoming series from the Chinese University Press of Hong Kong. Among his translations of Latin American poetry and prose are the Collected Poems of Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges’ Selected Non-Fictions, Xavier Villaurrutia’s Nostalgia for Death, and Vicente Huidobro’s Altazor. A large collection, The Poems of Octavio Paz, will be published this fall. His work has been translated into thirty languages, and appears often in the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books.

Photo by Nina Subin.

Additional research by Kelly Roberts.