Four Poems by Donata Berra with an introduction and translations by Charif Shanahan

Donata Berra’s work came to me by chance. I had just moved to Switzerland for love. I had just begun studying at the University of Berne, where Donata teaches. I had wandered, at random, into the Romance Languages building, bumped into a nice man in the Italian department who, I would later discover, was a poet, too, and found myself enrolling in an Italian course. Course: Advanced Italian Syntax and Grammar. Instructor: D. Berra/Staff.

Donata Berra’s work came to me by chance. I had just moved to Switzerland for love. I had just begun studying at the University of Berne, where Donata teaches. I had wandered, at random, into the Romance Languages building, bumped into a nice man in the Italian department who, I would later discover, was a poet, too, and found myself enrolling in an Italian course. Course: Advanced Italian Syntax and Grammar. Instructor: D. Berra/Staff.

After two weeks, longing already for literature to complement the linguistic focus of the course, I asked Donata if she could make recommendations of Italian poets to read in addition to the course work. She obliged, indicating that she was actually a passionate reader of poetry. She told me she loved many of the same English-language poets I loved, though she had only read them in translation. She told me that it would be her pleasure to help; in fact, she would bring me her personal copies of the books she recommended so I wouldn’t have to navigate the library stacks. She never mentioned she was a poet.

Each week, Donata brought me books, and each week, I took them home, devoured them, and gave them back to her in class, where we discussed compound reflexive pronouns and the passato remoto. To the final class, Donata brought a thin, red collection of poetry, which lay, face down, on the desk next to her. I was surprised: I didn’t know that I would see her again after this class and therefore hadn’t been expecting a book. After the lesson, she handed me the collection, her own, with humility and graciousness, saying only that she hoped I liked it.

I say with embarrassment that A memoria di mare /As the Sea Remembers sat on my bookshelf for two years before I opened it purposefully. I discovered a collection marked by a palpable sensuality of language, arresting imagery, and a tremendous sensitivity to the human condition—to the great tragedies that unite us, and to the nuances of even our smallest interactions. Moved, without thinking, I found myself translating Donata’s most powerful poems. I deliberately stayed as literal in my translations as possible, wanting to preserve, and to transmit, the clarity of voice, scene, and affect in these poems.

—Charif Shanahan

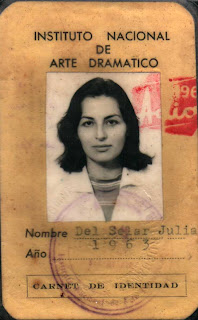

photo of Donata Berra by Yvonne Böhler

Tsunami

by Donata Berra

Quando sull’arco del giorno si schiaccia la notte

e abbruna la linfa alle nostre membra sfatte

passa la mano dell’onda e subito

abbiamo tutti lo stesso nome

i giochi le reti gettate gli sguardi la compiacenza

il lungo, faticoso metterci in scena

niente più appare

sotto il cielo ragnato da un inutile sole

come se il tempo si trovasse altrove

calma è soltanto la voce

nostra, che dice – in fondo noi

lo sapevamo.

Vieni, riposa, voglio accarezzarti di buio,

buio sulla tua pelle, a piene mani ti accarezzo

di buio

che renda cieca la voce.

Tsunami

by Donata Berra

As the night presses onto the arc of day

and darkens the lymph in our undone limbs

the hand of the wave passes and instantly

we all have the same name

the games the cast nets the gazes the complacency

the long, tiresome staging of ourselves

nothing appears anymore

beneath the sky spidered by a useless sun

as though time itself was somewhere else

only our voice is calm,

it says – in our deepest selves,

we knew it.

Come, rest, I want to caress you with the dark,

dark on your skin, with both hands I caress you

in the dark that blinds the voice.

translated from Italian by Charif Shanahan

more>>

Tsunami

by Donata BerraQuando sull’arco del giorno si schiaccia la notte

e abbruna la linfa alle nostre membra sfatte

passa la mano dell’onda e subito

abbiamo tutti lo stesso nome

i giochi le reti gettate gli sguardi la compiacenza

il lungo, faticoso metterci in scena

niente più appare

sotto il cielo ragnato da un inutile sole

come se il tempo si trovasse altrove

calma è soltanto la voce

nostra, che dice – in fondo noi

lo sapevamo.

Vieni, riposa, voglio accarezzarti di buio,

buio sulla tua pelle, a piene mani ti accarezzo

di buio

che renda cieca la voce.

Tsunami

by Donata BerraAs the night presses onto the arc of day

and darkens the lymph in our undone limbs

the hand of the wave passes and instantly

we all have the same name

the games the cast nets the gazes the complacency

the long, tiresome staging of ourselves

nothing appears anymore

beneath the sky spidered by a useless sun

as though time itself was somewhere else

only our voice is calm,

it says – in our deepest selves,

we knew it.

Come, rest, I want to caress you with the dark,

dark on your skin, with both hands I caress you

in the dark that blinds the voice.

translated from Italian by Charif Shanahan